Subtitle:

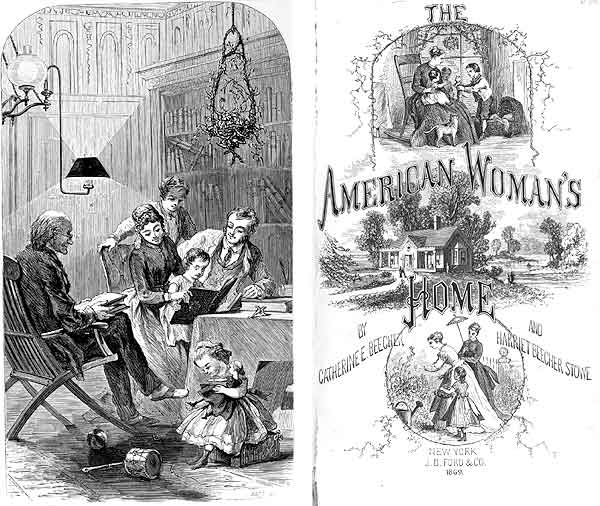

Being a Guide to the Formation and Maintenance of Economical, Healthful, Beautiful and Christian Homes and dedicated to the women of America in who hands rest the real destinies of the Republic*

Original Publication Date: 1869

Genre: non-fiction

Topics: cooking, housekeeping, health

Review by Liz Inskip-Paulk (http://ravingreader.wordpress.com/):

The wise woman seeks a home…, she will aim to secure a house so planned that it will provide in the best manner for health, industry, and economy, those cardinal requisites of domestic enjoyment and success.

Meet the original Martha Stewarts…

This was a mid-Victorian American best seller of domestic advice and was a successful collaboration between two sisters, Catharine E. Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe (younger sister of the two). Their mother died when Catharine was 16 and Harriet was five, and Catharine took over the running of the house then. She became a teacher during her 20’s and was engaged to be married but her fiancé died at sea before that could happen. Instead, she started a school for girls which included a more rigorous “male” education than usual. Catharine was instrumental in promoting schools out west in the US pioneer territories.

Interestingly, Catharine did not believe that women should have the vote, but then so did a lot of other people at that point in time. (The National Woman Suffrage Association was founded in 1869, and Wyoming was the very first state to give women the vote, so it was an ongoing political battle at that point.)

Younger sister Harriet was a mover and a shaker in the abolitionist world (especially for the writing of Uncle Tom’s Cabin), and the U. S. Civil War had only just finished a few years ago before this was published, and would be fresh in the cultural memory. Also, the Emancipation Proclamation and 13th Amendment were recent historical events as well.

Harriet was the seventh of 13 children (including six brothers who all became ministers), and was lucky enough to be educated in the school that her older sister founded (see above). She married a preacher/theologist and moved to northern Florida where she started one of the first integrated schools in the country. Both Harriet and her hubby were involved in the Underground Railroad at times.

This particular book is very detailed on many levels with the aim of elevating “housekeeping” to a domestic science, and admittedly, there is a lot of science talked about here – serious science as well on a variety of topics ranging from heat conduction/convection, how we breathe, how furnaces and stoves work, how cells form in the human body, the different chemical elements in the human body (wrt nutrition etc.). It’s really interesting to see how the sisters matched domesticity with hard scientific fact here, and it’s clear how hard they had both worked to make this a serious reference book for women in the domestic sphere (and out) – perhaps trying to elevate the humble art of making a home?

Loaded with such intricate details to help inexperienced wives or housekeepers with few servants (if any), this is a pretty comprehensive handbook. Details are included to help readers make their own furniture or house down to the type of nails and what should match with what… how wide the shelves should be in the kitchen… The kitchen sink was designed to be very shallow compared with today’s sinks (three inches deep was recommended with three feet wide)… Plumbing was important (as it still is today) and “must be well done or much annoyance will ensue”…

The physical health of the family, especially for a family far removed from urban resources, was vital, and this volume does not shy from the technicalities of the human body functions. It goes into some depth about human breathing and heart and the importance of fresh air (especially in crowded houses in winter) – The authors state that “they are informed by medical writers that defective ventilation is one great cause of diseased joints, as well as of diseases of the eyes, ears, and skin…”

It’s important for women to know how to care for the health of her family: To a woman of age and experience, these duties often involve a measure of trial and difficulty at times deemed almost insupportable; how hard, then, must they press on the heart of the young and inexperienced!

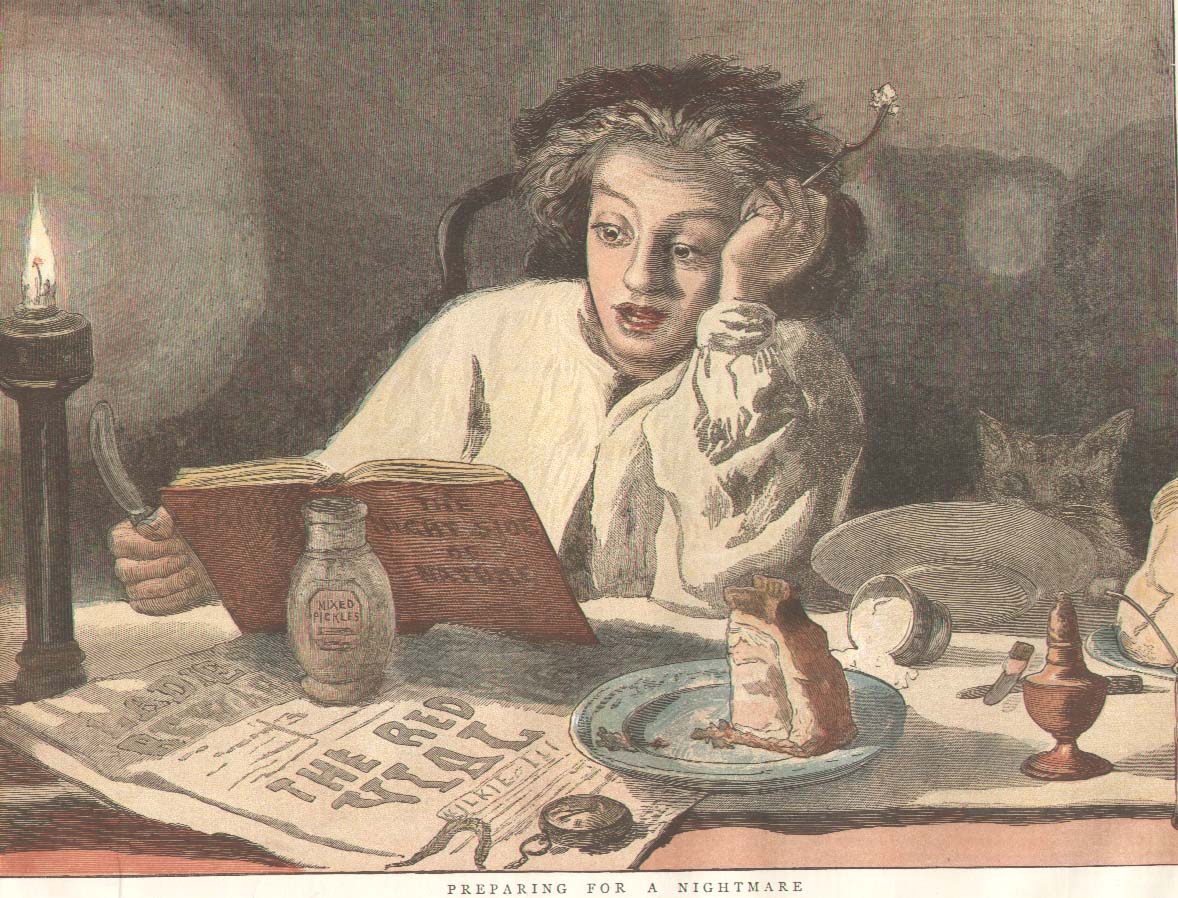

Watch out for too much learning as “the thinking portion of the brain may be so overworked as to drain the nervous fluid for other portions which become debilitated by the loss… the overworked portion may be diseased or paralyzed by the excess…” Victorians would also believe that education negatively affected a woman’s uterus and fertility so watch out for that…

This also holds for staying busy by being active: “the heavenly pleasure secured by virtuous industry and benevolence, while it satisfies at the time, awakens fresh desires for the continuance of so ennobling a good”… Getting up early is a very important trait (as seen in the aristocracy in England, it seems) and it’s important the young America avoids this “aristocratic folly”… (It’s also, for reasons unknown, portrayed as more patriotic to get up early in this land of ours.)

Having a beautiful home “contributes much to the education of the entire household in refinement, intellectual development, and moral sensibility”… It even offers lists of art to buy and maintains that having a beautiful house is also important for the ongoing education of the children of the establishment: The educating influence of these works of art can hardly be over-estimated. Surrounded by such suggestions of the beautiful, and such reminders of history and art, children are constantly trained to correctness of tote and refinement of thought, and stimulated…

Such sly-witted opinions are put in subtly every now and then: (with reference to the practice of growing ferns in the house to add color) - “we have been into rooms which…have been made to have an air so poetical and attractive that they seemed more like a nymph’s case than any thing in the real world…” (Watch out for greenhouse ferns as they are expensive and “often great cheats … and die on your hands in the most reckless and shameless manner…”

As for the quality of food, as the authors state, “the American table, taken as a whole, is inferior to that of England or France”… chortle. Yorkshire pudding for all! (French people and their cooking (their niceties and French whim-whams!) are described (for unknown reasons) as “seemingly thoughtless people” – what brought that comment about? Rather different perspective than Julia Childs, methinks… But no recipes were included which was curious. Perhaps the authors didn’t want to venture into that “women’s” territory with this project.

And I liked this bit: “Yet in England,… their perfect cooking is as absolute a certainty as the rising of the sun…”

American cookery books get a bit bashed here: “Half of the recipes in our cook-books are mere murder to such constitutions and stomachs as we grow here…” so it’s perfectly OK to swipe tips from other countries (notably France and UK, it seems). Curiously enough, the authors are very conscious of being American and try extra hard to show that America (young as the country was) still had its own merits. They are quite concerned about being “as good as” other countries (notably in Europe).

Back to the kitchen…. Beware of using pepper, mustard and spices – they “quicken the labors of the internal organs” … “a person who thus keeps the body working under an unnatural excitement [using such spices], *live faster* than Nature designed, and the constitution is worn out just so much the sooner…” At the same time, beware of cold foods (such as ice cream) as the stomach needs to have a certain degree of warmth or it “ceases to act….” And if you’re going to eat whale oil, add sawdust to give it heft.

Despite its age, the book offers some very valid advice though, still applicable today: The fewer mixtures there are in cooking, the more healthful is the food likely to be… the idea of growing local (of course since transport was difficult), and eating for appetite and due to exercise etc. as opposed to just sitting down at the table and gobbling everything there is. Lots of fruit and veggies etc. but watch out for the evil potato as it belongs to a “family suspected of very dangerous traits…” (i.e. deadly nightshade et al.)

As for serving cold bread, the authors report: “the unknown horrors of dyspepsia from bad bread are a topic over which we willingly draw a veil…”

Healthy drinking choices were also covered, including the hazards of using stimulants (alcohol, opium mixtures, tobacco, tea and coffee). This habit often goes to “such an extreme that the passion is perfectly uncontrollable, and mind and body perish under this baleful habit…” (Chapter 10.) Tea is not left out either: Drinking hot tea can lead to loss of teeth (as a study from Mexico demonstrated – drinking tea at almost boiling point was the chief cause of the “almost entire want of teeth in that country..and it cannot be much doubted that much evil is done in this way by hot drinks”…

However, a later chapter reports really positively on drinking tea with the following: “The first article of … faith is, that the water must not merely be hot, not merely have boiled a few moments since, but be actually boiling at the moment it touches the tea. Hence, though servants in England are vastly better trained than with us, this delicate mystery is seldom left to their hands. Tea-making belongs to the drawing-room, and high-born ladies preside at "the bubbling and loud hissing urn," and see that all due rites and solemnities are properly performed—that the cups are hot, and that the infused tea waits the exact time before the libations commence.”

Fashion - according to the authors, wearing tight corsets may lead to dreadful ulcers and cancers… In fact, the authors conclude that “the horrible torments inflicted by savage Indians or cruel inquisitors on their victims or the protracted agonies that result from [using confining corsets etc.] sometime the former would be a merciful exchange… and tender parents are unconsciously leading their lovely and hapless daughters to this awful doom…”

I do think that quite a lot of people would benefit from reading chapter Fifteen (about manners). What’s interesting is that both the Beechers argue that people in America are too repressive in their expression of feelings, and they need to loosen up a bit, but I think that that’s been overcome by people now. J

The Beechers also make rather a radical point for the time: that husbands need to honor the wishes and happiness of wives as of equal value of his own – I’m not sure how popular that sentiment would have been with the Average Guy back then.

Related to being polite to people is also a whole chapter on keeping your temper when you’re a housekeeper – “There is nothing which has a more abiding influence on the happiness of a family than the preservation of equable and cheerful temper and tones in the housekeeper.” So you remember that as you’re cooking dinner for ten on an unpredictable stove in a far outpost on the Pioneer Trail in a dust storm….

And on the handbook goes – principles and advice about almost everything from giving to charity, saving time, taking care of infants and the “aged”, what to do if someone gets struck by lightning, lighting a fire, propagating plants, how to build and maintain an “earth closet and its excrementitious matter”… (That’s not a typo there…)

I think this book must have been HUGE to hold and read (or published in multi-volumes) as it has so much info in it. This was a fascinating journey into the housekeeping world of the nineteenth century of Victorian America, and if you are remotely curious about how earlier generations of women maintained their houses, this is for you. Great to dip in and out of….

* “dedicated to the women of America in who hands rest the real destinies of the Republic” – this reference is very striking as it seriously undermines the current thinking of that time (i.e. that women could not be smart/powerful/involved in politics). By phrasing this “in whose hands rest…”, the Beechers smartly make a point without sounding too “aggressive” for the people who were threatened by increased female involvement in society. Nice tricky touch by the sisters there.

Download

The American Woman's Home by Catharine E. Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe at

Project Gutenberg|

The Historic American Cookbook Project

Original Publication Date: 1905

Original Publication Date: 1905